Do you want to use external flash to take your photos to the next level?

You can.

In fact, one of the most efficient ways to give your photography a bit of extra oomph is with artificial lighting. And it’s really not that hard—at least, not once you know some basic flash guidelines.

That’s what this article is all about.

First, I’m going to talk to you about choosing a flash.

Then, I’m going to explain how you can use that flash to get gorgeous light.

Finally, I’m going to give you some practical tips for working with one, two, or even three off-camera flashes—to create amazing photos.

Let’s get started.

External Flash Photography:

When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a commission at no cost to you. We evaluate products independently. Commissions do not affect our evaluations. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

What Is External Flash in Photography?

An external flash (also known as an off-camera flash) refers to a speedlight, like this:

They’re small, portable, and they’re not part of your camera. They run on batteries (usually AA batteries).

External flashes contrast with your camera’s built-in flash—the pop-up flash, which you should never, ever use, no matter what, because it looks terrible (more on that later!). The pop-up flash is integrated into the top of your camera, and it flips up when you hit the flash icon.

An external flash, however, can be mounted onto the top of your camera (using the camera hot shoe). Or it can be mounted to a light stand, a small flash mount, or even nothing at all.

Note that off-camera flash can also be contrasted with studio strobes, also known as monolights. These are much more powerful than external flashes, but they’re also far less portable; you have to plug in a studio strobe or bring a power pack, which involves a whole new level of inconvenience.

For beginners, or for pros who prize portability, an external flash (or two, or three, or four) is the way to go. External flashes offer a lot of power at a very reasonable price, plus they’re nicely portable. Whereas a studio strobe comes with a huge price tag and a lot of annoying restrictions.

What Can You Do With a Flash?

If you’re coming to flash for the first time, you’re in for a treat.

Because a single speedlight can make a huge difference to your photography. It can be that a-ha! moment, when you realize you can do all sorts of cool things and that it’s not even difficult.

What sort of cool things am I talking about?

First, you can create very natural looking shots no matter the ambient light. You can shoot in early morning, at night, during the day, in shade, and much more. Because you have a powerful light source you can control, the quality of the ambient light just doesn’t matter much. And it’s pretty easy to cancel out the ambient light by heading into a darker area—which lets you have complete lighting control.

Second, you can create high-key backgrounds without much trouble at all. I’m talking ultra-white backgrounds that look very fresh, modern, and cool, like this:

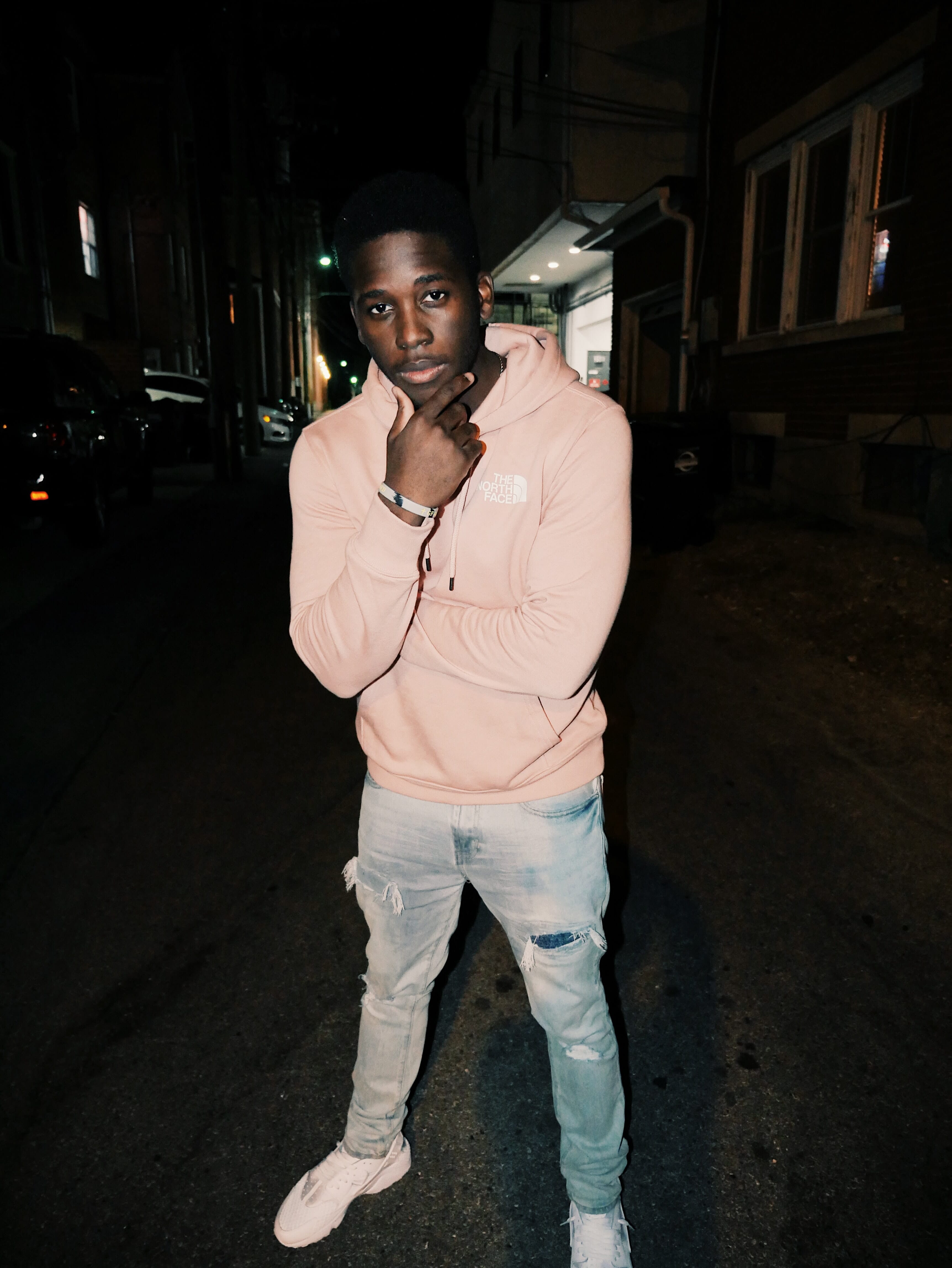

Third, you can create low-key backgrounds with ease. Low-key backgrounds are completely black, like this:

And low-key backgrounds are fantastic for giving your shots a very moody aura.

Fourth, you can use a flash to create wonderfully flattering portrait light. You can sculpt features by shooting from different angles, you can create dramatic light, soft light, rim light, you name it.

Now, the list above is hardly exhaustive. But I’m hoping you have a sense of the power of flash, and what you can do with a bit of flash knowledge.

I’ll talk more specifically about how to pull off some of the techniques I mentioned above, but first let’s look at how to pick a flash:

Choosing the Perfect Off-Camera Flash

If you’re looking for an off-camera flash, there are a few basic factors you’ll want to take into account.

First, you’ll need to consider price. While speedlights aren’t nearly as expensive as professional-quality lenses, they can cost a considerable chunk of change. While there are budget options, these come with compromises, primarily in terms of build-quality and longevity.

My suggestion is to start out purchasing a couple of cheaper flashes. While these may not last you as long as a dedicated professional speedlight, it’ll give you a chance to get your feet wet, and to ensure that yes, you really do want to pursue flash photography (because if you don’t like using flash, you’re not going to be happy with the money you spent on three high-end speedlights!)

Once you’ve become familiar with the basics of flash, and once you’ve really started taking flash photography seriously, you can start upgrading your setup to include higher-end flashes.

Bear in mind, though, that a flash is a flash. Unlike lens quality, which does depend heavily on price, the actual light that you get from cheap speedlights is going to look very similar to the light you get from more expensive speedlights. So you don’t have to worry about all your early pictures being ruined by a cheaper flash.

Make sense?

Once you’ve established your flash budget, you’ll want to think about the flash itself. If you plan on using the flash for high-speed photography, where you’ll need to fire off multiple shots in a short period of time, a fast recycle time is a must.

(Recycle time refers to the amount of time it takes for a flash to reset, so it can fire again at full power.)

Flash power is represented by the guide number, and is another key feature to consider. The guide number indicates the power of the flash—how bright is its maximum setting?

If you’re working in a small studio setting, the ability to fire off an ultra-bright flash might be less important. But in an outdoor environment, or when shooting events where you can’t always get as near to your subject as you’d like, a large guide number is key.

You’ll also need to think about flexibility. Some flashes don’t allow the flash head to be tilted or rotated, which seriously limits your options as a photographer. I recommend staying away from this type of flash, and instead searching for a flash that offers tilt and swivel capabilities.

Third, you should ask yourself:

Do you care about through-the-lens (TTL) metering?

While TTL metering is a topic that deserves an article of its own, it’s basically a way to hook up your flash to your camera’s exposure meter. In other words, your camera and flash work together to determine the proper exposure, and choose settings accordingly. This is in contrast to a flash used manually, where you dial in the flash power independent from the camera settings.

Personally, I use my flashes manually, and I recommend that you do, too. Manual flashes aren’t actually difficult to use, and they can ensure greater exposure accuracy once you get the hang of them. Whereas TTL flashes tend to be pricier but not worth the extra money. Later in this article, I’ll talk about how to use a flash manually to set the exposure.

Finally, you should think about flash compatibility. If you do decide that through-the-lens metering is a necessity, then you’ll need to choose a flash that’s compatible with your camera’s TTL. If you decide to fire your flash using a wireless trigger (as discussed in the next section), you’ll want to make sure your flash is compatible with the wireless trigger you use. If you want to fire your flash without a wireless trigger, then you’ll need to have a flash that has wireless compatibility with your camera.

Now that you know about choosing a flash, it’s time to look at the key flash accessories:

Choosing the Perfect Flash Accessories

Technically speaking, you can purchase a flash, mount it to the top of your camera (or on the included cold-shoe), and be done.

But I advise against this, because all of the cool stuff you can do with flash involves using the flash in various positions, not by mounting it onto the camera or on a tabletop cold-shoe.

In fact, for the same reason that I recommend you never use a pop-up flash, I suggest you never mount your external flash to your camera hot shoe. Direct light (that is, light that’s on the same axis as the camera lens) pretty much never looks good.

So what do you need in order to mount your flash elsewhere?

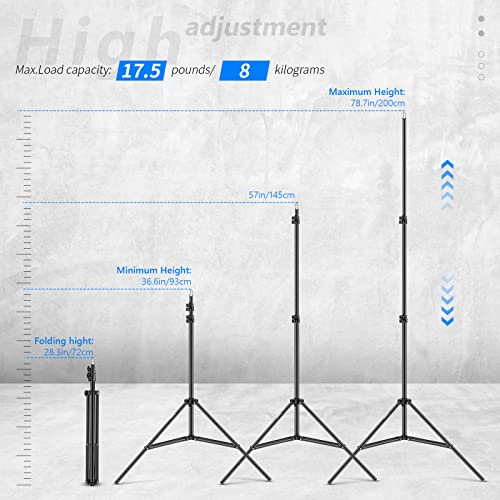

A lighting stand, a flash mount, and (maybe) a remote.

A lighting stand is like a tripod for a flash. It’ll let you position your flash anywhere you desire—in front of your subject, to the right, to the left, behind your subject, etc.

A flash mount attaches to a lighting stand, and it includes the mount you use to attach your flash. It also may give you additional tools, such as an umbrella holder (which is useful for attaching an umbrella to your flash, as I discuss below).

Fortunately, lighting stands and flash mounts start pretty inexpensive. While there are highly durable, professional-quality options on the market, you don’t need to pay to premium that this requires. Instead, grab a few sub-$20 lighting stands and a couple of $10 flash mounts and you’ll be all set.

A flash remote allows you to trigger your flash from your camera—when the flash is off sitting on a light stand somewhere.

Whether you need a flash remote depends on one key question:

Does your camera wirelessly allow you to trigger your flash? Depending on your camera brand and type of flash, this might be possible—so that you don’t have to purchase any special equipment, you just have to hit the shutter button on your camera and your flash will go off.

If your camera doesn’t allow you to trigger your flash wirelessly, then I recommend you pick up a flash remote. This generally mounts to the hotshoe of your camera and triggers as soon as you hit the shutter button. Note that you may also need a second piece of equipment, which attaches to the flash itself and responds to the remote, depending on the compatibility between your remote and flash.

One more accessory that I recommend, but isn’t required, is a reflector. You can pick up a nice 5-in-1 option from Neewer, which will give you a lot of flexibility:

Reflectors are great for bouncing light back onto your subject, plus the 5-in-1 reflectors include other cool features, such as a diffuser that you can hold in front of your flash for softer light.

If you’re on the fence about getting a reflector, here’s what I’d say:

If you’re only purchasing one flash, then a reflector is a great complementary piece of kit.

If you’re going to grab two or three flashes up front, then a reflector is nice, but less necessary.

Note that you can create DIY reflectors pretty easily. So you don’t have to feel hemmed in by the price of a 5-in-1 reflector. All you need is a bit of white cardboard and something to hold it up with. A book, brick, or other heavy object works in small-scale studio setups—when photographing products or still lifes, for example.

The final set of flash accessories that you’ll need are flash modifiers.

Modifiers are a key topic in off-camera flash photography, so I devote an entire section below to the ins and outs of flash modifiers.

But for now, just realize that flash looks bad without something placed between it and your subject. So you’re going to need to invest in at least one modifier.

For beginners, I recommend a white umbrella. Though if you’re willing to spend an extra few bucks, you can grab an umbrella that allows for multiple setups, like this:

The Fundamentals of External Flash

You know all about flashes. You know all about flash accessories.

But how do you actually create great shots with a flash?

This section is all about getting your flash up and running so that you can start taking stunning shots. I’m also going to talk about the different types of light you can create with a flash.

Let’s dive right in, starting with:

Setting Up Your Flash to Capture Photos (Manually)

Once you have a flash, it’s pretty easy to start using it straight out of the box.

You’ll want to first turn on your flash and configure it so it works with your flash setup. If you’re using a flash remote, you’ll want to attach this to your camera and make sure it’s set up to trigger the flash. If you’re triggering the flash through your camera itself, make sure that everything is working properly.

At this point, you’re going to need to understand the key flash feature:

Power.

Flash Power

Flash power refers to the brightness level of your flash.

Flash power is generally written in fractions, often from 1/128 all the way to 1/1.

1/128 is a lower power setting. Your flash will be very dark.

1/1 is a high power setting. Your flash will be very bright.

Make sense?

You can dial in the flash power on the back of your flash, or potentially via your flash remote. Note that every time you halve or double the power, you’re increasing or decreasing the brightness by a factor of two. So if you go from 1/2 to 1/1 power, you’re doubling the brightness. And if you go from 1/64 to 1/128 power, you’re halving the brightness.

Now let’s look at how you can actually use brightness to capture a perfect exposure:

Exposing With Flash

Exposure with flash is like regular exposure with any camera—except that you’ve now got a fourth variable to think about beyond aperture, shutter speed, and ISO:

Flash power, detailed in the previous section.

I recommend you select your camera settings using Manual mode in advance, and then leave these settings as they are. You should adjust the exposure of your shot only using flash power.

Shutter speed is an almost irrelevant variable when using flash, because the only light that matters is the light from the flash. So you should choose a shutter speed at your camera’s sync speed (usually around 1/200s) and leave it at that.

When using flash, you should have plenty of light. So you can set your ISO to the lowest possible value (usually ISO 100 or ISO 200).

And when using flash, you won’t need to maximize aperture to let in light. Flash provides lots of light. So choose the aperture based on the needs of your particular image.

If you’re not sure what aperture to choose, f/8 is a good starting point.

So, up to this point, you should have a shutter speed of around 1/200s, an ISO of around ISO 100, and an aperture of around f/8.

Now it’s time to set the final exposure variable, your flash power.

It’s pretty easy once you get the hang of it. Just set a power level of 1/16, then take a photo. See how it looks. If it’s too dark, brighten the flash to 1/8. If it’s too light, darken the flash to 1/32. Keep experimenting until you get the precise look you want (and you can use smaller increments on your flash to fine-tune the power setting).

Nothing too complex, right?

Types of Flash Lighting

When learning about flash photography, you’re going to here lots of talk about the different types of flash lighting.

Specifically, flash photographers distinguish between hard light and soft light.

Hard light looks contrast-heavy. It creates sharp transitions between areas that are well-lit and areas that are shrouded in shadow.

Soft light looks much more subtle. It creates soft transitions, and shadows tend not to be as harsh.

A naked flash—that is, an unmodified flash—will produce hard light. It looks like this:

While hard light occasionally works to give a cool, high-contrast look, it’s often better to use soft light (which is the primary form of light used by flash photographers).

And you can create soft light by adding modifiers to your flash.

Note that the bigger the modifier, the softer the light that will be produced.

Flash Modifiers Explained

There are several common types of flash modifiers, and plenty of uncommon flash modifiers.

So I’m going to hit on a few key options that every beginner should know about, and you’re free to research more particular flash modifiers as they become important within your own work.

First, flash umbrellas mount in front of your flash, and can either modify light that goes through the umbrella fabric, or modify the light by reflecting it off the umbrella fabric.

A white translucent umbrella softens the light by diffusing it.

While a silver umbrella is meant to work as a reflector.

Translucent umbrellas are probably the most basic flash modifier out there, and are great for beginners. They’ll take your flash and create a beautiful soft look, though they also spill light everywhere, so aren’t as good for capturing scenes where the direction of the light is essential.

Silver umbrellas are more punchy and create harder light, so I suggest you avoid these as a beginner.

Second, softboxes are another basic flash modifier. They go over the flash and put some nice white (diffusing) material in front of the light. While diffusers won’t give you quite the same level of softness as umbrellas, they’re better at directing the light.

There are also larger softboxes/diffusers that will give you beautiful, soft light. They sometimes come in the form of stripboxes (which are tall and very rectangular), or in an octagonal shape, like this:

Third, grids are good for cutting down the light spread, though they won’t do much to temper the hardness of a flash. So you can use a grid to create a spotlight effect, or to prevent light from falling on the background, but you won’t end up with a very soft result.

Snoots are similar to grids—they don’t decrease light harshness, but they’re great for creating very selective lighting effects, where you need to narrow the beam of light to a single spotlight.

Here’s the bottom line:

For a beginner, an umbrella is a great starting point. It’ll give you a chance to work with softer light, will cost very little, and can get you stunning shots.

Softboxes, grids, and snoots all have their place, but I recommend waiting until you’ve become more familiar with flash before exploring these options in earnest.

Creating Directional Light With a Flash

Now that you know how to modify a speedlight, I’m going to show you what you can actually do with your flash.

I’m going to start out with the different types of lighting, then go into common flash lighting setups.

Sound good?

Frontlight

The most basic type of flash lighting is direct frontlight.

This is what you get when you put your flash directly on top of your camera and fire away.

It illuminates the front of your subject entirely, leaving no shadows on the most prominent features, but heavy shadows in the object’s crevices, like this:

As you can see, frontlight doesn’t look great. The lack of shadows causes the shot to lose all depth.

That’s why you should avoid direct frontlight as much as possible.

One type of light that’s a bit more common is high frontlight, where you put the flash above the subject and shoot down.

This often isn’t ideal, but it can sculpt a person’s cheekbones for an interesting look. It’s often combined with a light that comes up from below a person to fill in the shadows under the chin, eyes, and nose.

45-Degree Lighting

45-degree lighting is extremely common in portrait photography.

You create 45-degree lighting by putting your flash off-camera, about 45 degrees to your right or left.

This illuminates your subject nicely, while also adding depth with some shadows:

You can create a very ‘window light’ effect by putting the light up above the subject, too (this is often called 45-45 lighting).

Sidelight

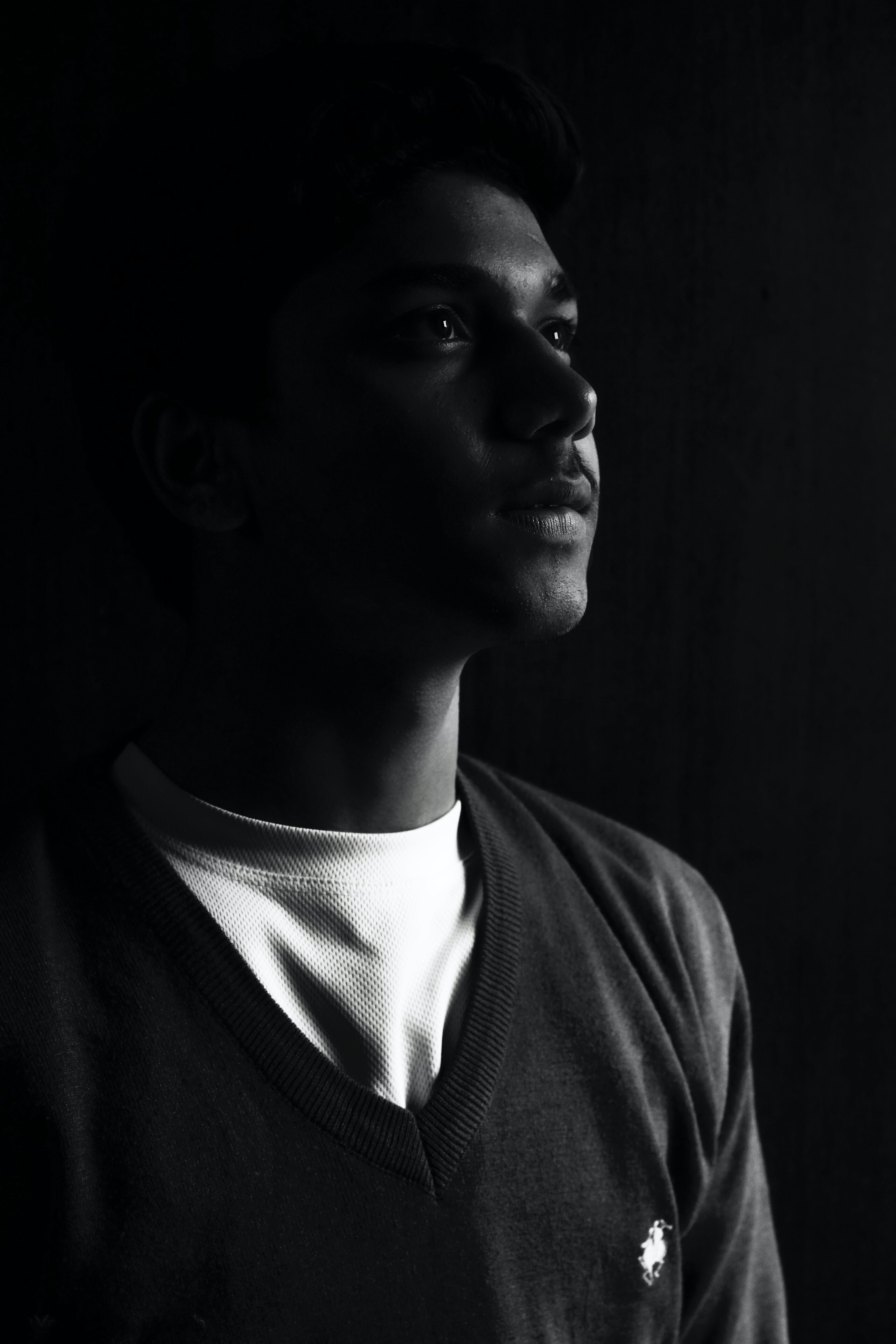

Sidelight comes from the side of your subject and tends to create a very dramatic look, like this:

This is because it casts heavy shadows on one side of the subject, while nicely illuminating the other. Sidelit photos often have a very dark background, because the flash falls off behind the subject (though it’s always possible to illuminate the background with a second flash).

There are various degrees of sidelighting, too—for instance, you can sidelight a subject completely (called split lighting), as used in the photo above.

Or you can bring the light out a bit, for less extreme shadows:

No matter which type of sidelight you choose, it’s a great way to add some drama to your photos, as well as depth. In fact, sidelight is very common in cinema for this very reason!

Backlight (Plus Rim Light)

Backlight is the most interesting type of direcitonal light, because it has so many different purposes.

Backlight comes from behind your subject, but it can be used to create various distinct effects.

For instance, you can position the light behind your subject (or slightly behind and off to the side) for a rim lighting effect, like this:

Rim light is very dramatic and can work well as a standalone effect, or to add more depth to the scene by making your subject pop off a dark background.

You can also put a large sheet of white paper behind your subject and point your flash toward it, in order to create a bright, high-key effect. It’s is great for product shots, as well as portraits with a bright and cheery feel.

Finally, you can put a flash behind a transparent subject to give a cool outlined effect while avoiding reflections. This is commonly used with glass, where you just don’t want to deal with pesky reflections and you want to create a very dramatic image.

Common Flash Lighting Setups: Practical Techniques for Amazing Flash Photos

While some flash photographers only work with one light, shot straight at the subject…

…it’s much more common to create a shot with light coming from different directions, and maybe even using multiple flashes.

In such scenarios, you’ll use one or several types of light mentioned above. You might combine 45-degree lighting with sidelight, or backlight with 45-degree lighting, or something else entirely.

So let me give you some practical lighting setups to try:

One-Flash Lighting Setups

If you only have one off-camera flash to work with, don’t fret!

Because you can create lots of amazing photos. I do recommend you bring a reflector into the equation, but it’s certainly not a requirement.

First, let’s talk about one of the most useful one-light setups:

45-45 Lighting

This one-light setup is simple, and it looks great:

45 degrees up, 45 degrees to the side.

I mentioned this type of setup above, but it bears repeating. Because it’s a great starting point when you’re doing photography.

You see, if you’re not sure how to position your flash to light a particular subject, 45-45 lighting is a good default. And then you can fine-tune the flash from there.

45-45 lighting will give you a shot like this:

It includes nice shadows, but nothing too heavy or too dramatic. And nothing too wild or out there.

If you use an umbrella with 45-45 lighting and you shoot fairly close to the background, you’ll end up with a visible backdrop. But you can rectify this with some cardboard that blocks the light behind your subject, or by moving your subject away from the background. That way, you’ll end up with a pitch-black background (for a very cool, low-key look!).

Split Lighting

Split lighting involves putting your single flash on the same axis as your subject, off to the right of you, the photographer.

It generally gives you a very dramatic, shadowy shot, like this:

See why it’s called split lighting? It splits the subject in two!

If you use an umbrella, the flash may throw light on the backdrop, depending on how close your subject is positioned. But if you’d like to avoid this, just bring your subject out a bit, and you’ll end up with a beautiful low-key photo.

Note that if you find split lighting to be a bit strong but still want to create a dramatic look, you can add a reflector in on the other side of the photo. This will punch up the shadows a bit without sacrificing the overall look of the image.

Rim Lighting

Rim lighting involves placing the light directly behind the subject, or slightly off to the side, for a silhouetted look:

But notice that rim lighting is not like a normal silhouette-style image.

This is because the background stays completely black, while only the subject itself is outlined. While this look is certainly unconventional, it can create very dramatic portraits, or interesting product shots.

Rim-lit photos can be enhanced with the addition of a colored gel, to give a blue rim, an orange rim, or anything in between.

Note that you can modify the level of rim by positioning the flash directly behind the subject or over to one side. So you can create a tiny edge rim, or you can create a broader rim, like this:

Of course, you can also combine rim light with other types of light for more frontal detail in your subject, but that’s something that I discuss in the next section:

Two-Flash Lighting Setups

While it’s absolutely possible to create stunning, professional-level images with a single light…

…it often pays to add a second light. With two lights, you can illuminate your subject beautifully – while also adding depth, dimension, and other cool effects to your images.

Generally, your second light will support the first. So you can often start with a one-light setup (discussed above), then add a second light for an even stronger image.

But note that, even if you don’t have two lights, you can often create the effect of a second light using a (store-bought or homemade) reflector. You just have to be careful with your positioning.

Let’s take a look at a few specific two-light setups that guarantee amazing results:

Clamshell Lighting

Clamshell lighting gives an in-your-face look that is both visually stunning and easy to produce.

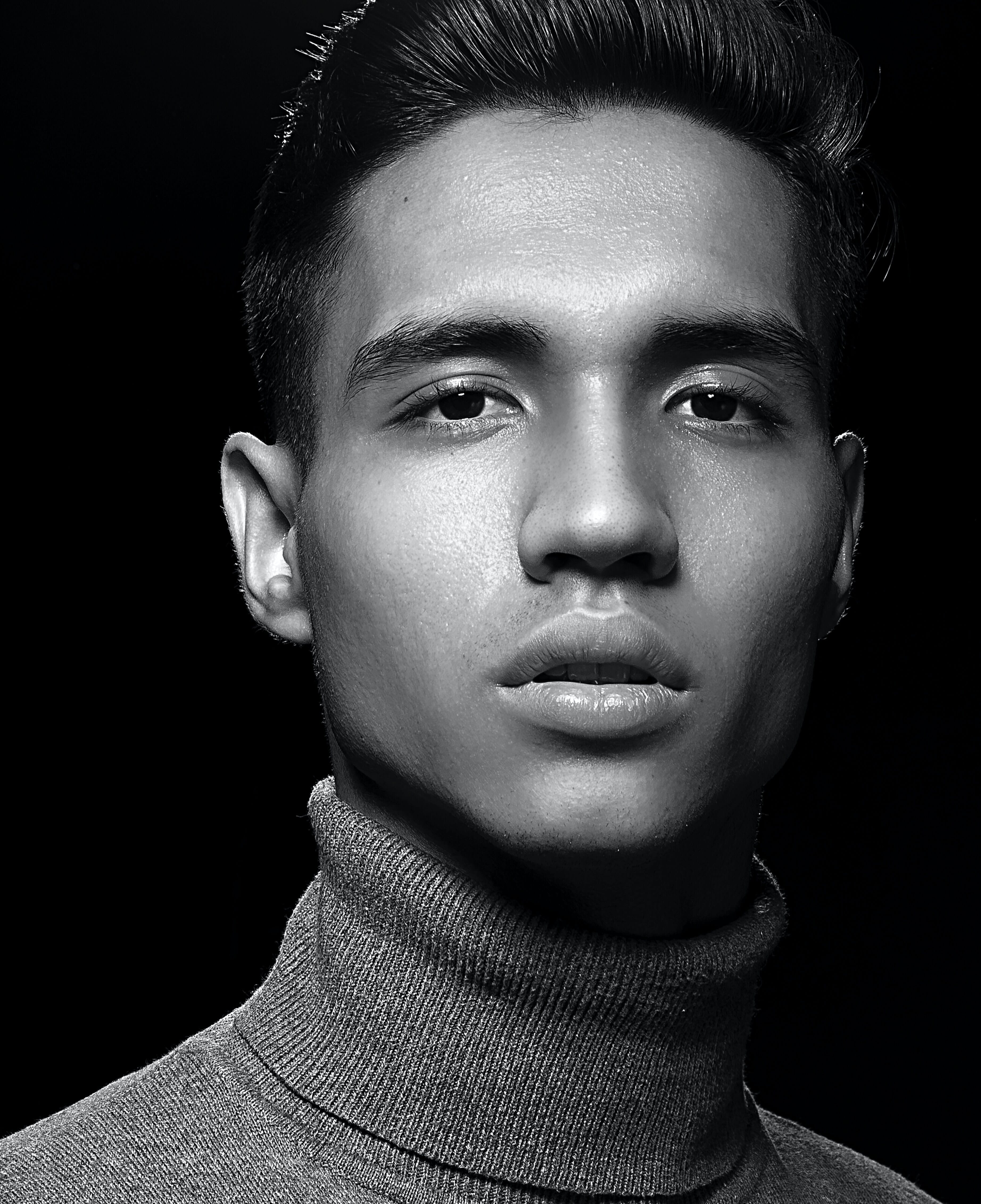

Here’s how a clamshell portrait looks:

Notice the strong lighting on the subject’s face and the lack of shadows under the subject’s chin?

That’s the power of clamshell lighting.

Now, a clamshell setup is almost always used for portraits. First, you raise one light above the subject, directly in front, pointed down at an angle.

(This setup, without the second light, is known as butterfly lighting or paramount lighting, and is often used to light actors in Hollywood.)

Next, you’d bring a light under your subject, pointed up at an angle. This should act as the fill light, and it should be weaker than the main light; the goal here is to illuminate the areas under the subject’s nose and chin, without creating any sort of reverse-shadow effect.

Of course, you’re free to play with the relative power of the two lights, but it is important that the fill light is always darker than the main light (or, at the very least, equal).

That way, you can capture some gorgeous clamshell lighting shots!

One more thing to note:

As I said above, you don’t always need two lights to pull off two-light setups. And this is especially true for clamshell lighting; you can often get away with using a reflector instead of your second light. Just place the reflector down below the subject, pointing up, and experiment with different distances. In order to really obliterate the nose and chin shadows, you may need to move the reflector very close (though letting it hang back a few feet from your subject’s face can also create a very cool look).

45-45 Plus Fill Light

Many two-light setups work like this:

First establish the main light (be it 45-45 lighting, loop lighting, Rembrandt lighting, split lighting, or something else entirely).

Then add a fill light on the opposite side of your subject.

And that’s what this lighting setup is about (it’s one of my favorites!). Unlike a number of these setups, the 45-45 plus fill light configuration is quite versatile. You can use it for portraits, of course, but also for still life shots, product shots, and more.

So it’s a good lighting setup to have in your back pocket.

Here’s how it works:

First, raise one light so it’s pointing down at a 45-degree angle, then bring it off to the side, so that it’s hitting your subject from that 45-45 degree angle I talked about in the one-light setup section.

Next, add a lower-powered (fill) light on the other side of your subject.

While you can experiment with different placements for the fill light, start by sticking it perpendicular to the camera lens (so it’s hitting your subject from the side, as if for a split lighting setup).

That way, you can fill in any hard shadows caused by the 45-45 lighting, and the whole thing will just look soft and beautiful.

As with clamshell lighting, it’s important to keep the fill light dimmer than the main light – otherwise you’ll end up with strange, unwanted, unexpected shadows.

But by increasing and decreasing the strength of the fill light, you can get different effects, such as a very dramatic shot (with a low-strength fill light), or a very bright shot (with a high-strength fill light).

Make sense?

Cross Lighting

Cross lighting is unbelievably simple to understand, amazingly flexible, and impressively versatile.

It can get you shots like this:

And this:

And this:

You see, cross lighting simply refers to illuminating your subject with two opposite light sources.

So you might put one light directly in front of your subject, and one light directly behind. Or one light directly below your subject, and one light directly above. (Hence the amazing amount of versatility!)

However, there are a few popular cross-lighting setups that you can use over and over again for great results.

First, there’s the 45-45 cross light, where you position one light at the 45-45 angle, then add a second light opposite it, just behind your subject.

The first light will give your subject some nice, soft illumination, while the second light will give your subject a beautiful rim light effect, thereby creating depth.

Second, there’s the “athlete” setup, which is often used when photographing intense athletes (and you’re aiming to create a tough-looking subject).

Here, you take the modifiers off your lights in order to create a hard-edged look.

Then position one light off to the right of your subject (so its beam is perpendicular to the lens) and the other light off to the left of your subject (again, so its beam is perpendicular to the lens, opposite the first light).

The goal is to end up with an in-your-face shot, like this:

Now, I don’t recommend you try this setup when doing family portraits.

But for grittier, intense photoshoots, this type of cross lighting can work really, really well.

Subject Plus Background

If you want to really make your portraits and still life shots pop…

…then you need to light the background.

It’s the difference between a shot like this:

And a shot like this:

Do you see how there’s so much more depth in the second shot? That’s thanks to the subject-background separation (which is created by the subtle background light!).

So for a standard, two-light, subject plus background setup, here’s what you do:

First, bring your main subject away from the background, so that no light from your primary strobe can fall on the backdrop.

Then set up your main light in any of the one-light setups discussed above; 45-45 is always a good place to start, but you can also go for split lighting, or even a rim lighting effect.

Take your second light and shine it directly on the background. Note that the power of the light will effect the darkness of the background, so you can use a low-powered flash to make the background look dark gray, or a high-powered flash to make it look white.

Also, depending on the angle of the second light, you’ll end up with a light gradient (if you shine the light on the backdrop from the side) or a uniform circle (if you place the light behind your subject and aim it directly at the background).

And you can change the background look by modifying your light source in different ways. A snoot will give you a hard, controlled splash of light, whereas a softbox or stripbox will give a softer, broader background.

Unfortunately, this is one of those two-light setups that cannot be created with a single light and a reflector. You’ll genuinely need two lights – but once you try it, you’ll know that it’s absolutely worth the money.

Three-Flash Lighting Setups

If you’re after the most professional lighting setups, then I highly recommend you invest in three lights.

(There are also some four-light setups, five-light setups, and more, but three is a good number for complex, sophisticated lighting and won’t break the bank.)

As you’ll see in a moment, three light setups generally involve applying lights to clearly defined areas of the scene.

In other words:

Three lights are rarely all used in front of the model. Instead, you put one or two lights on the model, one or two lights on the background, and one or two lights on the model’s rim.

Make sense?

Also, if you do have a fourth or fifth light to use, recognize that you can combine some of these three-light setups pretty easily.

Subject Plus Two Background Lights

In the previous section, I talked about the subject plus background approach, and how it’ll create a pro-level image with lots of depth.

And it’s true:

Subject plus background works very well as a high-quality, two-light setup.

However, the two-light version of this setup, while nice, has a problem:

It’s tough to get a uniform background.

If you put the background light off to the side, the background will fade in one direction (i.e., it’ll appear as a linear gradient), which isn’t necessarily a bad effect, but it’s not what you’re always after, either.

And if you put the background directly behind the subject, you may not get the light breadth you’re after.

So what do you do?

You use two lights on the background, and one on your main subject.

Simply set up your primary light the way you need – again, 45-45 lighting is a great way to start.

Then place your other two lights on either side of your subject, out of the frame and shining on the background.

You can experiment with positioning and power, but the goal is generally to create a uniform effect. If you’d like to increase the size of the light beam, you can always move your lights backward, or you can add a modifier.

Personally, I’m a big fan of this three-light setup, though you may find the lack of fill light frustrating. Fortunately, you can always use a reflector in place of a fourth light, placed in a fill position.

Subject Plus Two Rim Lights

As with background lights, rim lights are a great way to add depth and dimension to your photos.

Also like background lights, while a single rim light is nice, it can create slightly uneven effects. After all, do you want a rim going all the way around your subject, or just over part of your subject? It’s going to depend on your intentions, which means that you should know how to adjust this at will.

So here’s a three-light version of the cross light/rim light setup I discussed in the previous section. It’ll get you a uniform rim light, one that separates your entire subject from the background.

Use a 45-45 light on your main subject.

Then place one rim light behind your subject on the left, and one rim light behind your subject on the right. Both lights should be pointed back toward the subject, and you’re free to experiment with different positioning – by bringing the lights in toward one another, you’ll create a smaller rim light halo, but by bringing the lights outward, you’ll expand the halo size.

I’d recommend you modify your rim lights carefully, by the way. Naked flashes can work (the hard light makes for a nice rim), but you can go for a softer – but still direct – effect using stripboxes. I’d recommend avoiding large, soft modifiers, such as umbrellas, because these will throw the light everywhere and you’ll lose the subtle rim effect.

Also, if you find that the rim lights are interfering with your shots, just know that you can always clone them out later, so don’t worry about it too much.

Do be careful, however, of flare coming from your rim lights; it’s pretty easy to ruin an image this way, so I recommend you always take a test shot or two before proceeding with your photoshoot in earnest. If you do notice flare, you have the option of shooting anyway and cloning it out later, or moving your rim light further away from the main subject.

Main Light, Fill Light, Plus Background Light

This is a pretty standard method of lighting, because it allows you to fill in both the subject and the background, and therefore achieve soft, flattering images with a lot of dimensionality.

Here’s how it works:

Light your main subject with your primary light. As always, a 45-45 setup is a great place to start, but you can always use split lighting, front lighting, or something else entirely.

Add in the fill light, which should sit at a lower power than the primary light, and should fill in shadows on the opposite side of your subject.

(If necessary, you can use a reflector!)

Finally, add in the background light, which should point directly at the backdrop and give it a nice glow.

As I’ve discussed above, by changing the position of the background light, you’ll get different background effects. You can create a gradient by bringing the light nearer to the background and letting it rake across the backdrop surface, or you can create a very uniform circle by putting the light directly behind your subject and pointing it up at an angle.

Ultimately, the goal is to make the subject pop and add atmosphere without overpowering the foreground – so just be mindful of your light strength, and all will turn out great.

Main Light, Fill Light, Plus Rim Light

Here’s your final three light setup, and it’s a classic:

Main light, plus fill light, plus rim light.

Note that this entire setup is focused on the main subject; no light is pointed at the background, which means that you’ll either create a low-key image, or you’ll need to position your main light so it spills on the background as well as the foreground.

(Personally, I like the low-key look and it’s easier to achieve, but it’s ultimately up to you.)

To create this beautiful three light setup, first position your main light (as 45-45 light, split light, frontlight, etc.).

Then add your fill light, which should go somewhat opposite the main light and boost any too-dark shadows.

Finally, add the rim light. You can set it directly behind your subject, pointed toward the lens, or you can set it off to the side and pointed back; these different approaches will give different effects, such as a more uniform halo (with the light behind your subject) or a halo on just one side of the subject (with the light off to the subject’s side).

As I’ve reiterated throughout this article, you can substitute in a reflector for the fill light. It won’t give you as much control, but it should punch up those shadows nicely.

Related Posts

A Guide to External Flash: Conclusion

Now that you know how to use external flash, you’ll be unstoppable as a photographer.

The key is to both practice and persevere; if you feel like you’re struggling with a particular lighting setup, don’t throw in the towel. Instead, keep at it, and you’ll get it eventually!

Ultimately, just remember that there is no single best lighting setup. The setups I’ve provided are pretty popular, but you shouldn’t feel compelled to use any of them. Instead, modify as needed to create the look you’re after!

Do I need an external flash for outdoor photography?

No, you definitely don’t need an external flash for outdoor photography. You can shoot with just natural light, assuming you go out at the right time of day (when the light is soft). Or you can shoot with natural light and artificial light. You even have the option of shooting with external lighting only, as long as your flash setup is powerful enough.

Is an external flash worth it?

An external flash generally is worth it. It’s a quick way to take your photos to the next level, as long as you’re willing to put in some real practice.

Do professional photographers use flash?

Some do and some don’t. First, it depends on the type of photographer they are; a studio portrait photographer is far more likely to use a flash than a bird photographer, and a landscape photographer is far less likely to use flash than a still life photographer. Second, some professional photographers like the effects that flash offers, whereas others prefer natural light. However, if you learn to work with flash and natural light, you’ll be able to accurately and honestly evaluate which lighting type works best for you.

Why should I use an external flash?

External flash is perfect if you’re looking to gain more control over your photos. With external lighting, you can create plenty of interesting effects, from silhouettes and rim-lit outlines to lens flair and black backgrounds. An external flash isn’t absolutely necessary for great photos, but it helps a lot .

Does an external flash make a difference?

Absolutely! External flash can make a huge difference, assuming you use it correctly. You can create drama, bring out details, enhance the background, and much more with just a bit of external flash. That’s why I highly recommend you take external flash seriously and start practicing as soon as possible.